Why does Chris Minns want to undermine a hard-won tenet of Australian democracy?

Seriously, what he is doing is fucked up, and I'll explain why

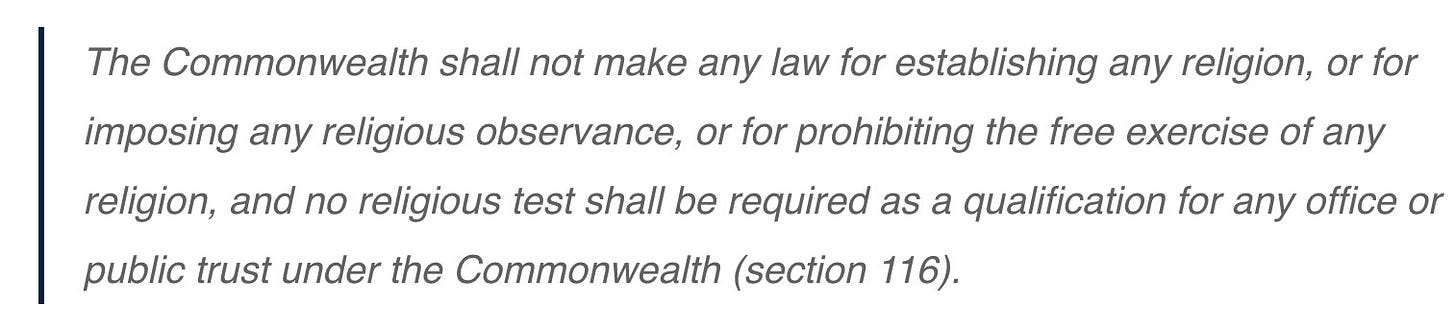

The separation of church and state is enshrined in Section 116 of Australia’s Constitution, though there is an argument that says that, rather than strict separation, what we have in Australia is a principle of state neutrality. This allows extensive cooperation between government and religious institutions while still prohibiting the establishment of an official religion.

We don’t need to get into the weeds with that argument to know that when a leading politician—in this case NSW Premier Chris Minns—holds a function inside Parliament House for the benefit of one particular religion and says stuff like, “In New South Wales, we rightly celebrate many important religious traditions. Yet, while most people in our state are Christian, this faith must not be forgotten,” he has crossed a line that shouldn’t be crossed.

Let me try and convince you why I think this is a big deal.

A bit of history before explaining why what Minns is doing is a big deal

Australia's distinctive approach to the relationship between church and state was shaped by colonial precedents, including Governor Richard Bourke's Church Act of 1836 in New South Wales. This allowed the government to support multiple denominations rather than privileging the Church of England, including providing subsidies for clerical salaries and church construction across Anglican, Catholic, Presbyterian, Methodist, Jewish, Wesleyan and Baptist communities. It created what experts call “plural establishment”, where the state recognises and supports multiple faiths rather than a single established church, as was/is the case in Britain.1

Section 116 emerged from debates during the 1897-1898 Constitutional Convention. Patrick McMahon Glynn—Federationist, politician and lawyer—successfully championed the inclusion of the phrase “humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God” in the preamble. Some participants, such as Henry Bournes Higgins, argued that the logic of such a preamble might grant Parliament implicit power to legislate on religious matters. Edmund Barton thought his argument was “far fetched”, but the amendment for including Section 116 passed, even if it was by a narrow margin of 25-16. The amendment meant that the Commonwealth couldn’t make laws to establish a religion, impose religious observance, prohibit free exercise of religion, or require religious tests for public office.

Still, at almost every turn, the High Court has interpreted Section 116 narrowly, and no law has ever been struck down for contravening its provisions. In Krygger v Williams (1912), the Court rejected claims that compulsory military training violated religious freedom. During World War II, the Adelaide Company of Jehovah's Witnesses case saw the government dissolve the organisation as prejudicial to defence, with the Court ruling this did not breach Section 116.

Arguably, the biggest challenge came in the 1981 DOGS case, where the Defence of Government Schools organisation argued federal funding of religious schools violated the establishment clause. The High Court unanimously rejected this. They ruled that Section 116 only prohibits establishing a particular religion as a state church, not general support for religious activities serving secular purposes like education. More recently, challenges to the National School Chaplaincy Program failed when the Court found chaplains did not hold offices under the Commonwealth.

And it isn’t just the courts who have rejected broader interpretations.

Two constitutional referendums attempted to extend Section 116's protections to state jurisdictions. In 1944, the post-war reconstruction referendum sought to extend religious freedom guarantees at all government levels. It failed. The 1988 rights and freedoms referendum again attempted to extend these protections, but it also failed having been opposed by religious schools and churches fearing it jeopardised funding arrangements.

A bit more history

From the earliest period of the colonial presence on the Southern Continent, sectarianism featured strongly, with the settlers/invaders reproducing the bitter divisions between Irish and English, Catholic and Protestant, which were to be found in Europe at the time.

Still, they also brought with them something of the growing Enlightenment moves towards toleration. Captain Cook himself was famously irreligious, a habit of mind that extended to his practice of eschewing religious references when naming landmarks, as was common amongst European explorers of the time. He preferred to use geographical features or the names of the great and the good from the mother country.2

Perhaps the single most relevant factor is that, despite (or maybe because of) the virulent sectarianism, the colony’s rulers recognised that religious strife was a recipe for chaos. “Caution, not indifference, characterises official attitudes to religion in the first years of European settlement,” Hilary M. Carey writes. “For those in a position of any authority in the late eighteenth century, particularly if that authority was exercised over mixed groups of Anglicans, evangelicals and Roman Catholics, religion was synonymous with civil disorder.”3

The civic understanding that underpinned the values of the new settlement was certainly Christian in nature, but it was imbued with a level of imperial practicality. Australia benefitted from its distance from Great Britain and there was no strong resistance to the official separation of church and state, ultimately reflected in section 116 of the Constitution, with all the provisos I have described above.4

I think it is fair to say that the burning religiosity that fired civic relations in the United States was largely absent in Australia and the sometimes-bitter sectarianism that regularly reared its head here, well into the 1960s, was often more about class and nationality than matters spiritual. Even John Howard makes this point in his autobiography:

Until the 1960s the ALP was the party of choice for the majority of Australian Catholics. Theology played no part in this; it was driven by socioeconomic factors, with Irish Catholics being predominantly of a working-class background. The sectarianism of earlier generations served to reinforce this alignment. Although the warming of Catholics towards the Liberal Party had begun in earnest with Menzies’ state aid gesture in 1963, the first Fraser cabinet of 1975 still included only one Catholic, Phillip Lynch. Over the coming years the dam would really burst on this old divide. One-half of the final Howard cabinet in 2007 were Catholics. Once again this had nothing to do with religion, it being the inevitable consequence of a socioeconomic realignment.5

Author Hilary Carey makes another great point when she says that a “remarkable feature of the Australian religious experience…is that so few new churches have been created here,” which stands in contrast to the United States and other British colonies in Africa, the Indian subcontinent, or Asia.

By the time of Federation, the Australian working class was amongst the most prosperous in the world and unionism seemed a more reliable path to a better life than religion. Amongst the intellectual class of the time, especially those associated with republicanism (largely through The Bulletin magazine), formal religion was another European hangover to be abandoned. Even well into the twentieth century, intellectuals and artists such as Manning Clark and Les Murray who openly expressed a faith were seen within their class as aberrations. Note, for instance, that academic Humphrey McQueen dismissed both in this regard, writing in his book Suspect History that “Clark made himself appear old-fashions—even loopy—by insisting on questions about the meaning of life. Had he not overheard that God was ceasing to exist?”

I’d argue that religious reasoning (faith) did not figure strongly in the intellectual idea of the nation and that the place quickly established itself as urban, coastal and secular in a way that was distinctive and certainly in contrast with the United States. Philip Drew notes in his book Coast Dwellers that the “concentration of people in a few major cities around the edge [of the continent] not only affects people’s daily lives and how they live, it also affects how they see Australia.” He, incidentally, contends that “the coast, not the outback, is central to the Australian imagination,” (and that is a culture war all by itself).

Minns is being reckless

Contemporary Australia has, then, achieved a hard-won pragmatic pluralism, where government and religious organisations cooperate extensively while maintaining formal non-establishment. The Commonwealth funds religious schools substantially, a practice that began with a decision by the Menzies Government in 1963. (That decision is largely seen as the end of the sectarianism that was rife throughout the nation until then and it is an outcome that Menzies himself saw as his most important achievement as prime minister.) The State also employs chaplains in various capacities, and all Australian parliaments open with Christian prayers.

It’s not a balance I am happy with, but it works well enough. We pay a certain level of official respect to religious plurality, but I don’t think anyone would deny that it is the Christian religion that still imbues our institutional presumptions and practices in a way that no other religion does. We still have the work of secularisation to do in this regard, but in the meantime, we shouldn’t fall for the argument that has undone America and given momentum to the Christian Nationalism currently trashing their democracy.

Separation of church and state doesn’t mean that politicians can’t be guided by their faith, but it does mean they can’t govern in a way that undermines the faith of others. It is not always an easy line to draw, but we must nonetheless draw it, erring on the side of pluralism.

Especially at the moment, our religious settlement remains fraught. All sorts of latent confrontations are closer to the surface than they have been in a while, including tensions and arguments around Israel and Gaza.6 If ever there was a time to cling to our functional separation of church and state it is now, and we should be loudly proclaiming its benefits, not letting politicians hold little parties in parliament for their Christian mates.

So, let me make clear, the separation doctrine guarantees religious freedom and protection for people of ALL faiths, and that is precisely its logic and strength.

It protects individual conscience and religious liberty by preventing state compulsion of belief while ensuring government accessibility to citizens of all faiths and none. It operates as a structural constitutional protection, similar to federalism and the separation of powers, allowing diverse religious and non-religious voices to participate in democratic debate.

Our system of governance derives authority from popular consent not divine mandate, and that consent requires justification through public reason rather than religious doctrines. This protects religious participation in the democratic processes while ensuring equal treatment regardless of citizens’ religious convictions.

When the Premier of our second-biggest State decides to have a special function inside the parliament and gives his support to the formation of an organisation dedicated to one religion at the expense of all others, he is damaging our chances of maintaining the much-lauded notion of “social cohesion”:

The Labor leader was among the political leaders and 50 Christian community leaders at the launch of the Christian Alliance Council of NSW, held at Parliament House, in Sydney on Friday 8 August.

According to a press release shared on the group’s social media, Premier Minns – a Catholic – “commended the gathering”, which was also attended by opposition leader Mark Speakman and former prime minister Tony Abbott.

“In New South Wales, we rightly celebrate many important religious traditions. Yet, while most people in our state are Christian, this faith must not be forgotten,” Minns said.

“Today’s gathering is a wonderful and long overdue celebration of our Christian heritage.”

The state’s minister for multiculturalism, Steve Kamper, said New South Wales was “made stronger by Christians”. Another Labor MP, Hugh McDermott, said Christian unity was “so important in today’s society”.

The Christian Alliance’s Facebook page described the event as “historic”.

“This is just the beginning. Together, we are committed to bringing Christians together and renewing the relevance of faith across our state,” it said.

After the rallies last weekend, the prime minister quite rightly implored the Opposition parties to not exploit such division for political gain. And yet, here we have a Labor Premier involving himself in an equally dangerous sort of division.

It’s a disgrace and we should call it out. (Oh, I just did.)

The main point is that unless people make the positive case for the fundamentals of a functioning democracy in our irreducibly and desirably diverse nation—and religious tolerance is high on that list—we are opening the door to those who would love to see such protections eroded.

What makes me really sick is that too often it is our so-called political leaders who are undermining such fundamentals, and we have to ask, to what ends?

See this piece by Nicholas Tonti-Filippini. (Note, it downloads automatically as a Word Document)

See Paul Carter’s difficult but interesting book, The Road to Botany Bay: An Essay in Spatial History (1987).

Carey, Hilary M.. Believing in Australia: A cultural history of religions (Function). Kindle Edition. (Great book.)

What’s the opposite of the tyranny of distance?

Howard, John. Lazarus Rising (p. 44). Kindle Edition.

Under such circumstances, it doesn’t help that Richard Marles is attending the so-called Mayors’ Summit Against Antisemitism, being held at a secret location on the Gold Coast, fully and lavishly funded by the pressure groups running the show. The aim is to have the restrictive and dangerous IHRA definition of antisemitism enshrined at the level of local government. As the Australia Jewish Council has said, “[I]t is a pro-Israel political junket designed to push a one-sided political agenda, silencing legitimate criticism of Israel by conflating it with antisemitism.” No Minister should be anywhere near such a transparent attempt to influence Australian decision-makers.

Minns is a reactionary in more ways than one. It is as if he considers his mission is to reset and restore, in his mind, the ground ceded by his Labor predecessors. Never mind that the world has moved on along with his electorate.

As I usually do TD - I reflect back on my own history. I was the child of a Seventh-day Adventist couple who in their childhoods (during the Great Depression) with family converted from Anglicanism to that narrow fundamentalist sect. Within which I grew up. At Sydney University in my second year (1967) I had my Education exam set for the Sabbath (Friday evening sunset till Saturday evening sunset) and the university made provision for me to sit sequestered with others - Seventh-day Adventist, Seventh Day Baptist and one Orthodox Jew - during that day - until the fall of evening permitted us to be moved to a location to sit our various exams with an invigilator to supervise us. Within the year I had resigned from that version of Christianity and explored several other faiths, Catholic, Anglican, Christadelphian - the latter so extreme and racist towards Palestinians that I went out immediately in search of the Qur'an and read it. I was surprised by how closely it matched The Bible (KJV) and the characters and stories within it. And I was very impressed by DOGS and at one point some years later (1978) worked alongside a woman who was Secretary of the organisation. I still strongly believe that sectarian-based schools should not receive any government funding. In fact I am opposed to all sectarian-based systems of education. I think enough public money has been given to those schools that it could be argued that they are now public and could be taken over into the public system. I see them as divisive and exclusionary to our society - an unhealthy concept of "private". (I'm think of schools operated by The Brethren, Jewish Schools, any religiously-based schools in fact - creating a sense of separateness or apartheid - based on their theological sense of superiority to others.) The engagement of Minns with the "suppository of wisdom" is most unfortunate. We are not a Christian society - and were not from the arrival of the First Fleet in January 1788. The chaplain to the Fleet was Richard Johnson a mate at Cambridge to William Wilberforce - he performed the marriage of my paternal ancestors just days after the women were landed in Warrane (Sydney Cove) a marriage that was ordered by Lord Sydney (Thomas Townshend) before their ship left Plymouth to join the rest at Portsmouth. Others of my family arrived on the ship the "Janus" with the first formally appointed Catholic priests to the colony in 1820. John THERRY and Philip CONNOLLY. Any prayers or references to formal religion within public contexts disturb me. Even if at the same time I have or have had friendships with priests and ministers - friendships enjoyed because of shared reconciliatory or philosophical social justice alignments. This is a very important essay, TD.