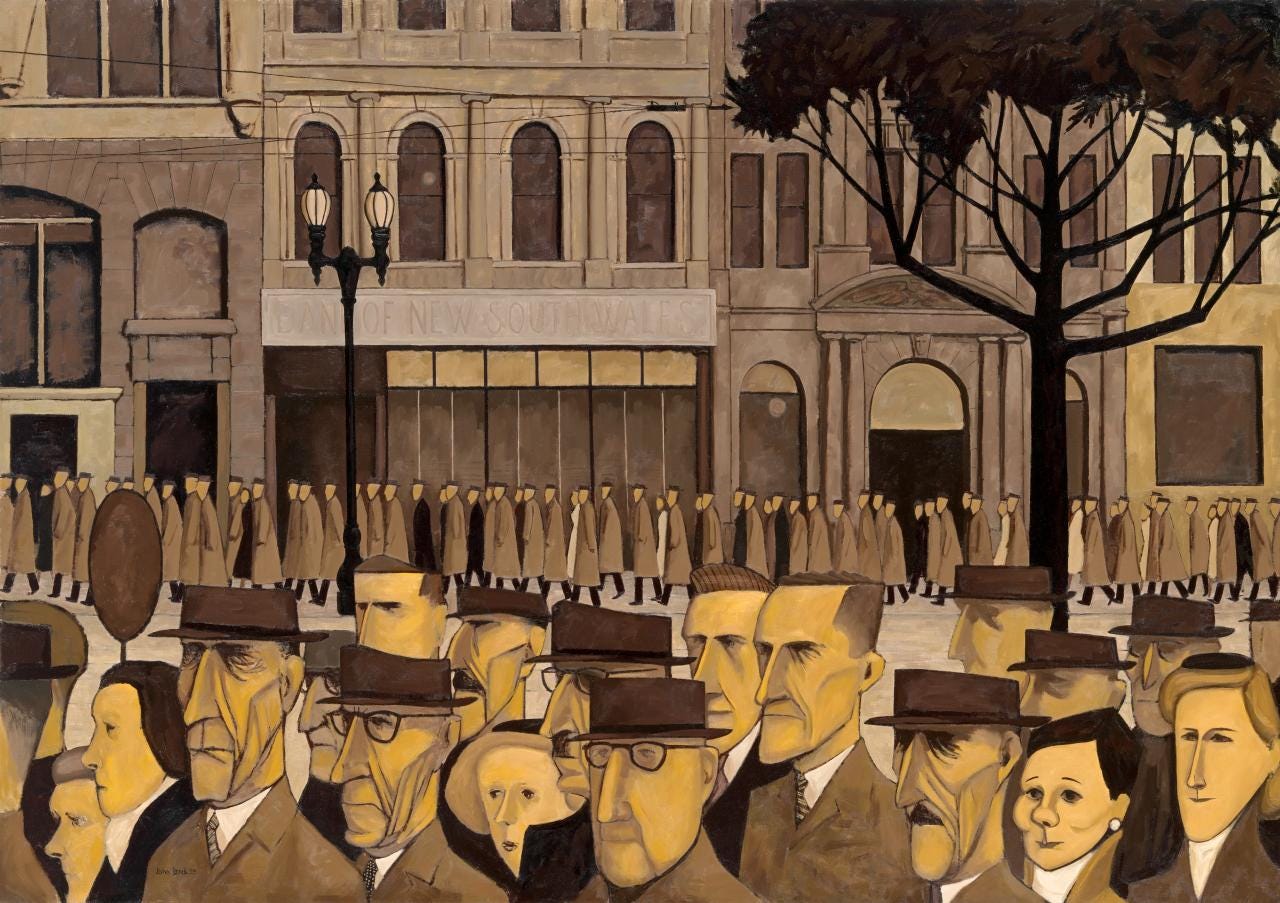

They had miles of proof that when Labor men got into power they had

forgotten the class that put them there. For twenty years they had been

urged to obtain Labor majorities. They had gotten those majorities, but

where was their heaven? ... Where were the golden streets? They could

see plenty of slums, of misery, of prostitution and poverty. They had been

following a vain dream and mirage.

Adelaide unionists, 1910, quoted in Jim Moss (1985) Sound of Trumpets

Let’s ease ourselves into the New Year. Or maybe not.

The 2025 election will be the last chance for the Labor Party to be at the vanguard of a new political settlement. If they end up leading a minority government after the 2025 election, it will be within their ability to reshape our political landscape and install themselves as the natural party government for the foreseeable future. They will be able to reinvent our parliament around a cooperative, deliberative m…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Future of Everything to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.