With Labor’s new laws on campaign financing now before the parliament—and Labor campaigning heavily on the idea that any attempt to amend any of their legislation is, by definition, obstructionism—there is a greater need than ever to sharpen our critique of the two-party system that those new laws seek to entrench.

The Electoral Legislation Amendment (Electoral Reform) Bill, which has the support of the Coalition Opposition and the Labor Government, is an attempt to subvert the way in which Australian voters are increasingly rejecting the major parties, and we must understand how we are being duped.

The language I am using here is strong, but we need something to snap us out of the bias two-party governance has forced on our political imaginations. We must make ourselves think outside that box.

Nowhere is that brain capture more apparent than in the constant habit of Australian journalists to imply, insist or presume that the community independents are somehow a party—calling them “teals” to strengthen that illusion—to suggest that they under some sort of central control by Simon Holmes a Court, or whomever, or that they are secretly aligned with one political party or another even if they are not a party themselves.

Party, party, party.

This way of thinking has become so habitual that it has rotted journalists’ brains, making it hard for most of them to see that other forms of democratic governance are even possible, let alone desirable. It’s pathetic. I mean, if you are going to claim that your job is to hold power to account, then there is no more important job than to question the primacy of the two-party system. So, let’s think about that.

Political parties are common to all democratic governments but they are not the same thing as democracy. Democracy does not require parties. It certainly doesn’t require two-party dominance.

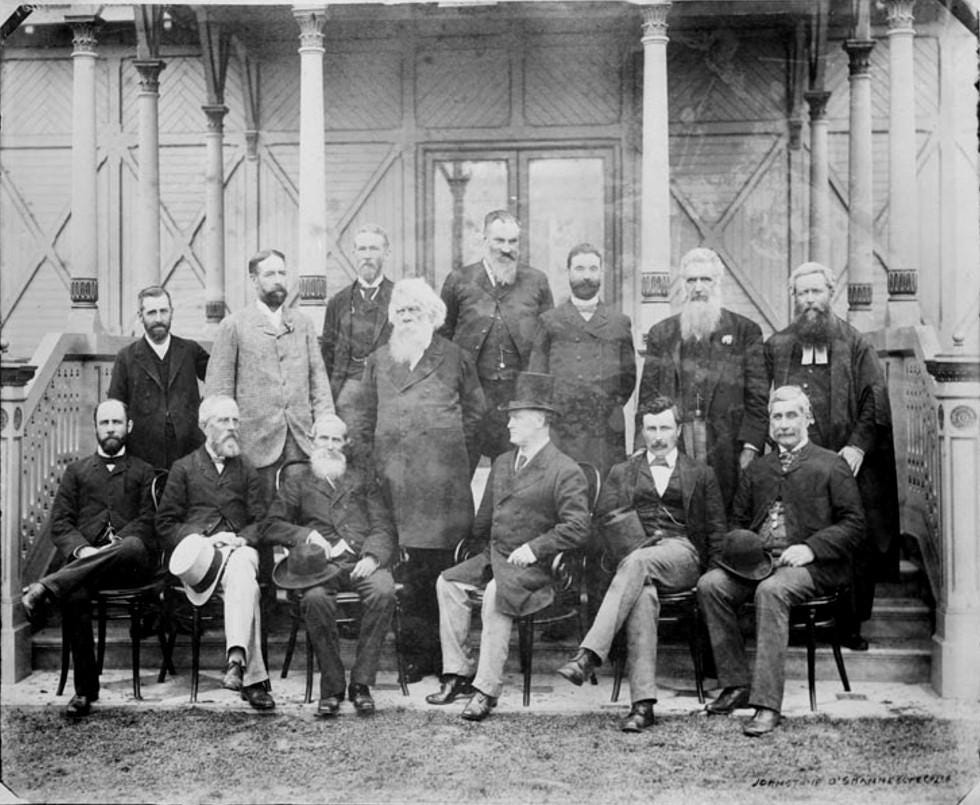

What’s more, the idea that parties are a problem is hardly new in Australia, and the Conventions of the 1890s that led to the formation of our federal parliament and the writing of our Constitution were full of participants debating ways to limit the influence of parties. If we knew more of this history, we would understand better that the idea of minority government—as we mislabel it now—was meant to a be a feature of the system of responsible government the founders were trying to achieve, not the bug it is presented as today.

The Convention delegates from the colonies (later to be states) spoke at length and with passion about avoiding the trap of party politics.

“Why should we have party government in the dominion parliament?” Colonel Smith, a delegate from South Australia asked. “I do not see the slightest necessity for creating two hostile parties in the dominion parliament.”

Chief Justice Higinbotham stated that “feelings of distrust and disapproval are, if I do not mistake, almost entirely occasioned and generated by the accursed system under which the party on this side of the House are always striving to murder the reputations of the party on the other side, in order to leap over the dead bodies of their reputations on to the seats in the Treasury bench.”

Mr W. McMillan from NSW noted that if people could get away from the party influence that was already a bugbear in the states, “They would be more likely to come together in a spirit of amity, and the common desire would be to do what was best for the country.”

Sir Henry Parkes suggested that the success of British parliamentary government was aided by the extent to which members ignored party loyalty, that British MPs “exhibited a higher sense of the interests of the nation to which they belong, and of the importance of good government, than of any party conflict.”

Sir Samuel Griffith, entering into debate on a number of the issues that concerned the delegates, suggested that “Constitutional government is not by any means the same as responsible government, and responsible government is quite a different thing from party government…[P]arty government is a thing of which we have had some experience in Australia, but which I am afraid is becoming somewhat discredited.”

Thomas Playford from South Australia made abundantly clear that “we shall endeavour to separate [the question of federation] distinctly from party politics. I can say for the opposition in South Australia, and for the ministry and their supporters, that that is what we intend to do. We intend to keep the question of federation altogether distinct and separate from questions of party politics.”

There are many other examples, but despite the concerns of the founders, they failed to inhibit the formation of dominant parties. From 1904 onwards, the Labor and non-Labor sides of politics not only aligned against each other but constituted themselves to usurp parliament’s control of responsible government to their own caucuses and executives. We have been living in the iron grip of these parties ever since, to the detriment of parliamentary democracy.

I’m not dismissing that early practice entirely out of hand, let alone saying it was all bad, just that it has run its course and we need major reform. The electorate that the two-party system sought to represent during that early period was much more homogenous than the nation we are today and the two-party consolidation that occurred after the general election of 1904 lined up pretty closely with the pro- and anti-Labor divide of the country as a whole.

But that homogeneity has now gone.

The rise of independents and a viable crossbench outside the two-party system is an inevitable and necessary response to that growth in diversity and we should be looking for ways to make it work rather than trying to stifle it.

Unfortunately, the new campaign laws before the parliament seek to bury our history and undermine this renewed debate. The new legislation is a contemptuous feint by the out-of-touch major parties to subvert the will of the people. Such laws would’ve been laughed out of the Constitutional Conventions that gave us our system of federal governance, seen for the con they are.

And here's the thing: the shift in people’s votes away from Labor and the Coalition is happening for a reason. Our party-dominated parliament is no longer delivering the once taken-for-granted quality of life that made Australia a beacon of comfortable aspiration. The two-party system is no longer responsive to electorates on any number of issues and it has reversed polarity: politics has become about parties inducing voters to conform with party policy rather than politicians listening to what people want.1

That’s the fucking problem.

This degeneration has been a long time coming, and we can trace its roots to the neoliberal turn of the Labor Party in the early 1980s, aided and abetted by the Accords that served to neuter worker power; and then through the Howard purges of his party’s “wets” during the 1990s, where the broad church of the Liberal Party was reduced to a right-wing rump which has only become right-wingier and rumpier ever since.

Perhaps there was a time when the majors could’ve saved themselves from irrelevance. But these new finance laws show that they have no real interest in the sort of reform that would make government more responsive to the legitimate desires of the electorate. Instead, they are trying to wield their parliamentary power to rig the system in their own favour in perpetuity.

How dare they.

Political scientist, Dean Jaensch got it right in his 1983 book, The Australian Party System:

Reform does not mean the abolition of parties [and] reforms can come only from the voters themselves: by increasing involvement in political life; by greater awareness of political events, structures and processes; by a willingness to go beyond the 'how-to- vote' cards at elections; by a realisation that politics does imping; on virtually every aspect of life in short, by a decrease of the level of apathy. In the final analysis, party reform can only come ‘from below’, from a conviction in the electorate that reform is necessary. The hope is that the voters in Australia are not overwhelmed by cynicism before this can emerge.

The rise of community independents is a version of the changes he imagined and their success has shown clearly that cynicism need not develop, that apathy can be overcome, and that Australians are now well-primed to enact the sort of reform Jaensch was talking about at the dawn of the Hawke era.

Sadly, we can no longer rely on the goodwill of parties to do the right thing.

Any hope we have for sensible reform will arise only if we vote Labor and/or the Coalition into minority government and then insist the resulting crossbench finds the courage to wield their power in the interests of the diverse nation we have become.

The party system also undermines our ability to become a republic, but that’s a discussion for another time. But just sayin’….

Totally agree, Tim. While the two old parties continue to play turn-and-turn-about, there will be no reform. It is not in their interests to do so. Retaining power is their only goal now. Plus their post-politics career...

I wholeheartedly agree, Tim. It's interesting that you wrote this today, as the Guardian published a Megalogenis article kinda-sorta admitting that minority govt might be what we need.

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2024/nov/25/i-used-to-think-australia-was-best-served-by-a-majority-government-now-im-not-so-sure